Arabica

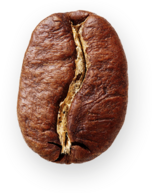

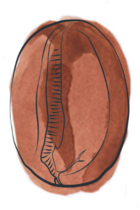

Botanical name: Coffea arabica

Origin: Ethiopia

Altitude: 800–2200 m

Temperature: 15–24°C

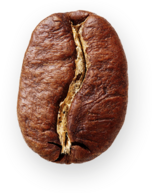

Shape: Oval, flat and elongated with an S-shaped centre cut

Flavour and aroma: Elegant, fine, fresh and fruity

Caffeine: 0.9–1.4%

We do everything for the perfect coffee pleasure. The coffee bean is our passion. This passion began with prodomo – and lives on to this day in every cup of Dallmayr coffee. From the coffee’s origin and the art of roasting, right up to the perfect preparation: we carry out our work with great care and a love for detail. The result is a level of quality that you can feel, smell and taste.

An espresso with a hint of cinnamon, a smooth caffè crema, or perhaps a strong filter coffee? Classic in flavour, such as Dallmayr prodomo? Or maybe a little spicier like Dallmayr Ethiopia? Coffee beans or coffee capsules? A sustainable coffee, such as Gran Verde? When it comes to the Dallmayr world of coffee, the possibilities are almost endless. We’ll be delighted to give you advice and help you find your favourite type of coffee. And maybe you’ll feel inspired to discover something new along the way!

Filter coffee

Espresso / caffè crema

Capsules

Pads

Instant

Search for product

Crema d'Oro

Home Barista Caffè Crema Dolce

Home Barista Crema e Aroma

Selection 2024

Crema d'Oro intensa

Espresso d'Oro

Crema prodomo

Home Barista Espresso Intenso

Home Barista Caffè Crema Forte

Gran Verde Café Crème

Espresso Barista

Espresso Decaffeinato

Espresso India Parchment Robusta

Espresso Monaco

Monaco

All caffè crema / espresso coffees

prodomo naturally mild

prodomo

Gran Verde Filter Coffee

Tanzania Gombe

Colombia Pink Bourbon

Costa Rica Single Estate

Ethiopian Crown

Hawaii Kona Extra Fancy

Jamaica Blue Mountain

Java Estate

Kenya Top Gakuyuini

Peru Amazonas

Sigri Estate

Guatemala San Sebastian

Cooperative Dano

prodomo decaffeinated

Ethiopian Crown

Antigua Tarrazu

Dyawa Antara

San Sebastian

San Sebastian special edition munich

prodomo

Classic

Classic kräftig

Classic mild

Ethiopia

French Press prodomo

prodomo Drip Coffee

All filter coffees

capsa Barista

capsa Belluno

capsa Lungo Selection Africa

capsa Boost

capsa Gran Verde Lungo Intenso

capsa Gran Verde Espresso

capsa Lungo Decaffeinato

capsa Espresso Decaffeinato

capsa Mild Roast

capsa Ristretto

capsa Azzurro

capsa prodomo

capsa Crema d'Oro

capsa Crema d'Oro Intensa

Cremesso Crema d’Oro

Cremesso prodomo

Dolce Gusto prodomo

Dolce Gusto Crema d’Oro

Dolce Gusto Crema d’Oro intensa

Dolce Gusto Crema d’Oro Latte

All capsules

Classic pads

Crema d'Oro intensa

Crema d'Oro

prodomo pads

All pads

Instant Gold

All instant

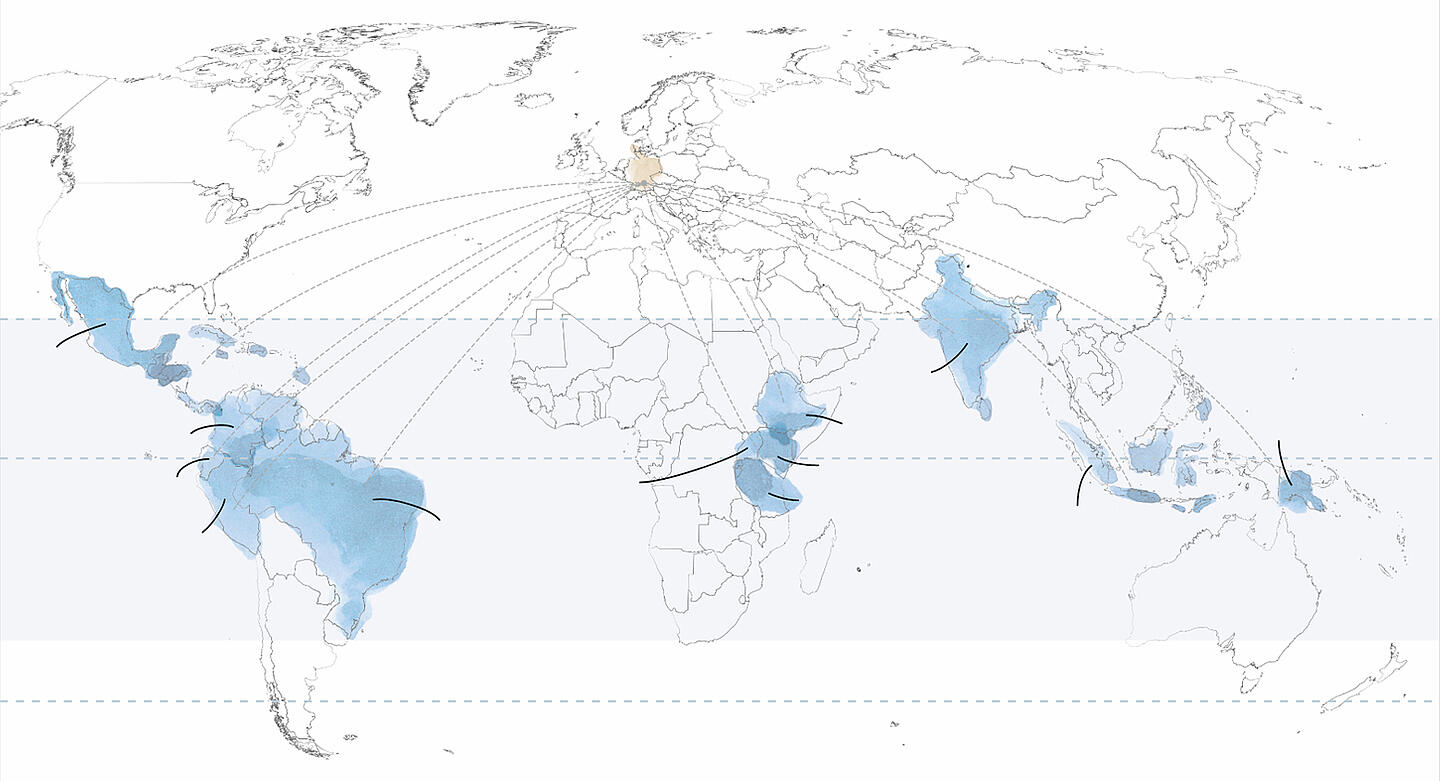

The best growing conditions can be found around the equator, in what is known as the coffee belt. Coffee grows exclusively in tropical and subtropical regions – from 23 degrees north to 25 degrees south of the equator. The coffee-growing regions within this area form an imaginary band – a “coffee belt” – that stretches around the globe.

The luxury commodity is cultivated in around 80 countries within this belt, although only some of them generate quantities of coffee that are economically significant. Brazil produces a third of the coffee traded on the world market.

Of all the different species of coffee, two are of particular importance: arabica (coffea arabica) and robusta (coffea canephora) make up 98 percent of the green coffee produced around the world. Of the two, arabica is considered the more sophisticated in flavour. It is grown at altitudes of up to 2,200 metres and is meticulously harvested by hand.

The higher the altitude, the cooler the average yearly temperature, and this allows the coffee cherries to ripen more slowly. They therefore have more time to develop their flavour, aroma and delicate acidity.

Botanical name: Coffea arabica

Origin: Ethiopia

Altitude: 800–2200 m

Temperature: 15–24°C

Shape: Oval, flat and elongated with an S-shaped centre cut

Flavour and aroma: Elegant, fine, fresh and fruity

Caffeine: 0.9–1.4%

Botanical name: Coffea canephora

Origin: Congo

Altitude: 0–800 m

Temperature: around 26°C

Shape: Small and round with a straight centre cut

Flavour and aroma: Smokey, spicy, earthy and woody

Caffeine: 1.8–4.0%

As with wine, a coffee’s character is influenced by a number of factors. The properties of the soil, the temperature, and the amount of rainfall during the ripening stage all have an impact on the coffee’s flavour.

The coffee tree is a sensitive plant. Not only does it require lots of care and attention, but it also needs a stable climate – during the day and at night. It needs sufficient rainfall and plenty of shade, and can’t deal with strong winds or extreme heat and cold. The ground should be rich in nutrients and good at retaining water – which is particularly the case with volcanic soil, for example. Generally, the higher the altitude of the coffee-growing region, the cooler the average yearly temperature. This allows the coffee cherries to ripen more slowly, giving them more time to develop their flavours, aromas and, in particular, their acidity.

Organic coffee is farmed using mixed cropping methods. So in addition to the coffee bush, organic plantations are also home to tall plants like the banana tree. These are called shade trees, as their high, thick canopy of leaves protect the sensitive coffee plants from direct sunlight and heavy rainfall.

Harvesting coffee is a little like picking cherries: red means ripe – for most varieties, at least. However, unlike fruits here at home, the harvesting period for coffee cherries is usually two to three months – or even four months for some varieties and locations. The time at which the harvest begins depends on where the cherries are grown in the “coffee belt” that runs north and south of the equator. To the north, the harvesting season typically lasts from September to December, while to the south it can stretch from April or May to August. And there’s activity between those times, too. Close to the equator, there is virtually no significant period of time between the first and second bloom of the coffee tree – and therefore the first and second harvests. For most of the year there’s a coffee harvest taking place somewhere in the world.

Learn more about the different options and methods for picking coffee here:

For the best-quality coffee, the coffee cherries need to be at peak ripeness when harvested. At this stage, the coffee’s aromas are particularly well developed and the beans inside the cherry are just right for further processing. If the cherries are unripe, they lack flavour and aroma, while if they’ve ripened too much, they risk falling victim to mould, pests or rotting.

The coffee cherry contains sugar and has a water content of about 60%, meaning that overripe fruit will quickly deteriorate and decay. Still, there is no perfect time to carry out the harvest: a certain branch may contain ripe and unripe beans together, sometimes with single blossoms in between.

In order to harvest the highest quantities of red, ripe coffee cherries, high-quality arabica coffees are hand-picked – a method also known as “picking”. Once a coffee cherry begins to ripen, it becomes overripe in 10–14 days. For this reason, pickers will go through the plantation multiple times with their baskets for as long as worthwhile quantities of beans are still ripening.

Many high-quality coffees grow in the mountains or have fruits that are difficult to reach. The amount that can be picked by hand can therefore vary between 50 and 120 kg per day. Fifty kilos of ripe coffee cherries are required for six to seven kilos of roasted coffee.

The amount each person can collect is significantly higher if the coffee cherries are not picked individually but stripped off the branch with one swift movement of the hand. This method is called “strip-picking” and allows each worker to collect up to 250 kg of coffee fruit a day.

Both ripe and unripe fruit fall directly onto cloths or tarpaulins on the ground, where they are subsequently collected. While strip-picking is faster at first, some of this benefit is lost due to having to clean and sort the beans later on. Robusta beans and medium-quality arabicas in particular are harvested in this way.

On very large, predominantly flat plantations – for example in parts of Brazil – the coffee is harvested with machines. Similar to a vineyard, the coffee trees are arranged in rows, allowing the machines to drive through with vibrating combs and shake the cherries from the branches. The fruit falls either into an integrated container on the machine or onto tarpaulins and cloths on the ground.

No matter whether selected individually by hand or machine harvested: due to a moisture content of some 60% and the sugar in its fruit flesh – also known as pulp – coffee cherries can quickly perish. If they are not processed soon after harvesting, the fruit can quite rapidly turn mouldy, rot or ferment. The pulp therefore needs to be separated from the two beans inside the cherry; that way, at the end of processing, we no longer have a sensitive fruit, but green coffee beans with a moisture content of around 9–13%. This means they can be stored, they have a stable structure and are largely ready for roasting.

During processing, the coffee cherries generally take one of two paths – with some being “wet” processed and others “dry” processed. Before either can happen, the beans are subject to one of several sorting steps. Any contaminating elements should first be removed to prevent a negative impact on coffee quality or damage to the processing machines. The different density of the fruits compared to elements such as branches, leaves or stones helps the sorting process – regardless of whether it is carried out by hand, with suction devices or separated by flotation in washing channels.

Whether a coffee is “washed” or “unwashed” (“the natural process”) offers some initial insights into its quality. After all, this isn’t just about washing the outside of the coffee cherries, but whether the coffee is subsequently wet or dry processed. The two terms refer to the methods of separating the coffee bean from the outer layers of the cherry. The work involved for each of the two methods differs considerably – and the quality of the beans isn’t determined until the end of the process.

The method chosen by the producer depends on a number of factors. “Wet” processing requires lots of water. This is more common in mountainous areas where arabica coffee is grown. Because wet processing requires more steps to complete, it is more suitable for coffees that command higher prices. This process also has an impact on the coffee’s flavour, as it allows a certain acidity to develop.

If the coffee hasn’t been picked individually by hand, then the unripe and overripe cherries, as well as dirt and foreign bodies, are sorted and removed. This process can be carried out by hand, using wind and sieves, or in water basins and washing channels where coffee farmers benefit from the different densities of ripe and unripe cherries. That’s because unripe fruits sink faster.

Various machines known as depulpers squeeze the fruit. If the coffee cherries are ripe, the skin and pulp burst, releasing the two coffee beans inside. These are now light-coloured and slippery, as they remain covered by a layer of mucus, parchment and silverskin.

A perfect breeding ground for bacteria, mould or dirt, the layer of mucus needs to be removed. The beans are therefore placed in a water trough, where enzymes break down this mucus in one or two days. The beans’ flavours and aromas continue to develop during this stage.

After fermentation, the broken-down layer of mucus (also called “mucilage”) can be easily washed off. Any further unwanted beans can be removed during this step, too. After washing, the robust parchment and thin silverskin remain on the bean.

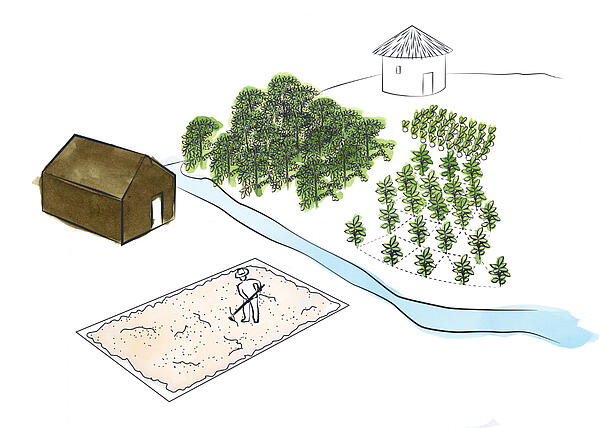

Drying stops the fermentation process. The beans in the parchment, or pergamino, are either spread in thin layers on the ground to dry in the sun, or mechanically dried in drums – just like in a tumble dryer.

Not surprisingly, dry processing requires dry conditions, which means it’s especially suitable for coffee-growing countries with reliable weather during the harvesting season. This process is used primarily with robusta coffees, which are strip-picked or machine harvested before being left on the ground for a few weeks to dry. The beans are characterised by their dark centre cut and a full-bodied flavour later on in the cup.

Since dry processing produces lower-cost coffees, the beans are usually strip-picked or machine harvested rather than selectively picked by hand. This means the harvest will contain a high proportion of unripe or overripe coffee cherries – along with leaves, branches and dirt.

Similar to wet processing, the purity and quality of dry-processed coffees can be increased by sorting the beans with sieves, air flow, washing channels or tanks with syphons. Robusta coffees and arabicas grown at low altitudes are often processed in this way.

The entire cherries are dried in around 14 days, when they have a moisture content of about 11.5 percent. In countries where the climate allows it, coffee farmers spread the cleaned and sorted fruit onto the ground to form a layer around five or six centimetres high. Any higher will increase the risk of mould – while a thinner layer makes little difference to how fast the coffee dries. About 40 kg of fresh coffee fruit is spread across each square metre.

The ground for drying should be flat and easy to work with, as the fruit needs to be turned with large rakes several times a day. Clay or asphalt surfaces aren’t suitable as they can transfer certain flavours to the coffee. Tarpaulins are commonly used to protect the harvest from dew or rain. It takes around two weeks for the coffee to dry to sufficient levels. It is then possible to hear the beans rattle inside the brown-black coloured dried hull.

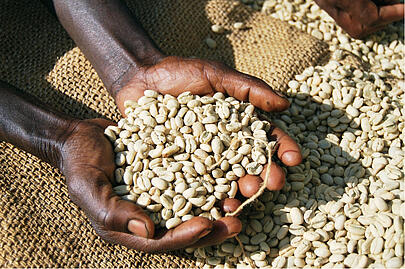

The dry or wet processed beans are rested for between one and two months after the first drying stage. They are still covered by dried fruit flesh or – in the case of washed coffees – the cherry’s parchment and silverskin. The green coffee traded on the world market looks different: these are the pure, unroasted beans. Which means that processing has to continue …

Next, the beans are hulled. The careful preparation up to this stage begins to prove its worth, as beans with the right moisture content can be separated more easily without splitting. Those still covered with their parchment – i.e. the wet-processed beans – have it removed mechanically. In the case of natural-processed beans, the dried fruit flesh has to be removed, too.

A number of further steps are required before the coffee can be sold and shipped. Here, sorting is key. After all, it’s not only the species and origin of the beans that influence the coffee’s price; it’s also important for the beans to be as uniform as possible. The more uniform the size, density and colour of the beans, the more precisely roasters can control the flavours and aromas that the coffee should have in the cup.

The aroma of freshly roasted coffee is simply irresistible. The smell of green coffee on the other hand is slightly reminiscent of hay. It is not until the roasting stage that the coffee’s flavours and aromas – of which there are around 1,000 – are unlocked from within the beans.

The green coffee that’s shipped to us in sacks or containers from the south is usually roasted at its destination. The quantity of coffee imported in roasted form is low – and is the exception on European supermarket shelves. On the one hand, this is to do with storage: processed green coffee can be kept for longer under controlled conditions before being perfected by the roasters. On the other hand, freshly roasted coffee loses its aromatic qualities after time; a coffee shipment from Colombia, for example, takes a very long time to reach us – and roasted coffee would inevitably lose some of its flavour.

More important still are the various tastes of the consumer. Even among Europeans, coffee preferences can be worlds apart. Sweden and Sicily for example are not just separated by a few thousand kilometres; they also have very different ideas about good coffee. The rule in Europe is simple: the further north the country, the stronger the preference for lighter coffee beans. Even within Italy, the very south of the country loves its espresso beans darker than people do in South Tyrol in the north.

The art of the coffee roaster lies in manipulating the green coffee to suit the wishes of the customer. In theory, a fruity and aromatic filter coffee for the north and an intense, tangy espresso for the south could be roasted from the same green coffee. The outcome wouldn’t always be perfect, as each green coffee has an ideal roasting level where it really comes into its own. But it would nevertheless be possible.

What’s fascinating is that dry heat and well-prepared coffee beans are all that’s required. The difference is down to the duration of the roast and the exact temperatures used. These are the factors that transform a hay-flavoured infusion into a universe of flavours and aromas.

Regardless of the method we use to transform raw beans into roasted coffee – in the end, it’s always down to controlling the temperature and duration of the roast to trigger the chemical reactions required for the desired flavour profile. At temperatures between 150 and 250°C, the proteins, peptides and sugars in the beans are converted into more than 1,000 volatile compounds. The interaction of these compounds is what gives the coffee its magical aroma. The process changes the structure of the beans, too, which double in size and become brittle.

Roasters have a number of methods at their fingertips, but the quantity of beans to be roasted is also very important. Is it the goal to create a delicacy from a single kilo of rare beans? Or should several tonnes of coffee be ready for the market within an hour? Should the beans be roasted slowly to remove certain levels of acidity? Or can the end product be exposed to higher temperatures in a shorter period of time? It’s not about playing with fire – but rather with really hot air: once they reach around 190°C, the light-brown beans break open with a popping sound and double in size. This “first crack” opens up a window during which master roasters can use their skills to create the perfect flavours and aromas. A good roasting level for our beloved filter coffee is reached shortly after the “first crack”. Roasting for another 15 minutes or so will lead to the “second crack”: the beans crack again, but this time not so loudly. Around the second crack is the ideal roasting level for an intense espresso.

In the drum roaster, the beans are roasted particularly slowly and gently in a slowly rotating drum. The drum is heated under controlled conditions from the outside. The contact between the coffee beans and the drum roaster’s wall, as well as the temperature in the drum, produces a very even roast. Drum roasters are available in a number of sizes. At Dallmayr, the smallest drum roaster roasts less than 100 grams per batch, while the largest one roasts up to 10 sacks of coffee at the same time.

Some roasters prioritise speed and large quantities, so they roast a continuous flow of beans. Using hot air at temperatures of up to 650°C, these machines roast the coffee in minutes. The long, tubular roasting drum looks a little like a concrete mixer: with each revolution, mechanisms inside the rotating roasting chamber transport the coffee a little further towards the end of the device.

Aerotherm is a special kind of batch roasting. Here, the beans are circulated inside the device by a stream of hot air and don’t come into contact with the roaster’s wall. This creates a particularly even roast. Around 20 kg can be roasted at a time, making this method particularly interesting for coffee rarities.

It’s not until the roasting stage that the beans develop the typical brown colour that we associate with coffee. Fruity acids develop in the first few minutes of roasting and break down as the process continues. In other words, the longer the beans are roasted, the less acidity there is in the final product. Roasting the coffee for longer gives the beans a more intense colour and flavour, creating the pleasant and bitter taste that is so typical of espresso.

The colour of the roasted beans will normally determine the way they are prepared later on. For example, the same light roast that produces a highly aromatic filter coffee would be fruitier and more acidic if it was prepared in an espresso machine. After all, just as roasting temperature and duration bring out certain characteristics in a coffee, the brewing temperature, water type and amount of contact with the water also release certain aromas.

Each coffee bean contains more than 800 flavours and aromas. Our noses allow us to differentiate between a vast number of aromas, which is in stark contrast to how our tongues perceive flavour (bitter, salty, sour, sweet, umami). The interaction of aroma and flavour – i.e. the combination of smell (aroma) and taste (with the tongue) – is what forms our overall impression of the coffee.

This is about comparing the mouthfeel and the finish (aftertaste). The “body” describes how the coffee feels in the mouth. For a better understanding of what this means, imagine how different water and milk feel in your mouth: the viscosity or fat content of the milk gives it more “body” than the water.

In a qualitative sense, acidity has nothing to do with being “sour” – i.e. with a badly brewed or roasted coffee. It actually describes a coffee’s fruity and tangy qualities. A delicate acidity is seen as a positive characteristic and a sign of high quality in a coffee. Acidity is particularly significant when evaluating arabicas. It lends the beans a certain brightness, freshness and dimension. A coffee without acidity tends to taste flat and bland.

· a filter cone and filter paper

· a jug for the coffee

· 30 g fresh, medium-fine ground coffee

· 500 ml hot water

brewing time approx. 3 min

· a French press (0.35 l)

· 20 g fresh, coarsely ground coffee

· 320 ml hot water

brewing time approx. 3 min

A simple way to influence the coffee’s flavour is to alter the brewing time. Darker roasts and a coarser grind size are particularly well-suited to this method of preparation.

· a stovetop espresso maker (also known as a moka pot)

· a damp cloth (optional)

· fresh, medium-fine ground coffee

· hot water

Towards the end of brewing, the coffee becomes watery and bitter in flavour. Putting a damp cloth around the lower section of the pot at this stage will stop the brewing process and prevent the coffee from tasting too bitter.

· a tamper

· a cloth or brush

· a portafilter espresso machine

· a conical or flat burr grinder with

very precise grind settings

· 8–9 g ground espresso for a single shot

or

· 16–18 g ground espresso for a double shot

Espresso flow is too slow and the coffee tastes too strong?

→ Then set the grind size to a coarser level, or use less coffee

Espresso flow is too fast and the coffee tastes weak and thin?

→ Then set the grind size to a finer level, or use more coffee

The espresso has a balanced, creamy flavour. The crema is golden brown and around 2 mm thick.

→ Well done! The perfect espresso!

A fully automatic coffee machine takes care of each and every step of the brewing process – from grinding the beans to preparing your espresso or café crème. The water is pushed through the freshly ground coffee at high pressure, creating a beautiful crema.

These convenient all-rounders are set up during manufacturing so you can start making coffee right away. However, we still recommend having the machine’s settings checked to ensure you get the optimum result in the cup.

· Grind size as fine as possible

· Brewing temperature around 90–92°C

· More coffee usually tastes better

· 25 ml of water for a single shot of espresso; around 150 ml for a caffè crema, depending on the cup size

At the Dallmayr Academy, you can learn all there is to know about the coffee bean – and how to make the best out of it. Click here to see our training programme and to register for a course: